Last #194s, as operated by Metro. Charles Powell photo

On Sunday, June 26, 2016, at 1:54 am, Metro’s Line #194 bus pulled up to the bus stop at Pomona and Temple, near the Cal Poly Pomona campus, discharged a handful of passengers, then “deadheaded” (traveled empty) back to its “home” at El Monte Station.

It would be the last time the orange-colored bus would serve this bus stop.

When service on Line #194 resumed a few hours later, it would be operated by the blue and white buses of Foothill Transit, the primary bus operator in the San Gabriel Valley.

Line #194, and its sister Line #190, were the last holdouts of Metro service in the eastern San Gabriel Valley. Some welcomed the transfer, others were opposed but resigned to it. However, few stakeholders—the passengers, drivers, mechanics, board members and administrative staff–of both Metro and Foothill realized this was just one more transformation in the long history of bus service in the San Gabriel Valley.

From A.R.G. and PE to “Metro”

The history of Lines #190 and #194 can be traced all the way back to the days of the “motor stages” of the early 1910s. Valley Boulevard, which closely patrolled the Southern Pacific rail line east of Los Angeles, had two competing bus services: the Clark Bus Line, which connected Los Angeles with Pomona, Ontario, and San Bernardino; and the A.R.G. Bus Company, which ran from Los Angeles to Ontario, then veered south to Riverside.

Motor Transit, which started in 1916 with a single route between Los Angeles and Anaheim via Whittier, acquired the Clark Bus Line in 1917 and A.R.G in 1920.

Meanwhile, Pacific Electric completed its rail between Los Angeles and San Bernardino in 1912. The “Big Red Cars” ran through El Monte, modern-day Baldwin Park, Covina, Pomona, Claremont, Upland, Fontana and Rialto. Ramona Boulevard ran near the PE rails as far as Baldwin Park.

Pacific Electric acquired Motor Transit in 1930, and shortly thereafter began to replace some of its rail lines with bus routes. PE’s San Bernardino Line was cut back to Covina in 1941, then cut further to Baldwin Park in 1947. Red PE buses replaced the former Red Car trips. By 1950, all passenger rail service on the San Bernardino Line had ended, and replacement buses operated via Ramona Blvd. to Los Angeles.

A Bus by Any Other Number…

The numbering history of these two lines is complex. PE rail or bus lines were unnumbered until 1943, when the Baldwin Park-San Bernadino route was designated #53 and the Valley Bl. route #57. Later in the year, both branches received the number #63.

In 1953, Metropolitan Coach Lines took over the remaining rail and bus operations of Pacific Electric. MCL renumbered both branches as Line #60. The Valley branch continued from Pomona to Riverside before serving San Bernardino, while the Ramona branch ran along Foothill Bl. between Claremont and San Bernardino.

Construction started on the Ramona Parkway (San Bernardino Freeway) in the early 1950s. The freeway replaced Ramona Bl. between Los Angeles and El Monte. Upon completion in 1957, buses running east of Pomona were routed onto the freeway, while buses only going as far as Pomona used either the Valley or Ramona Boulevard routes.

The California State Legislature formed the Southern California Rapid Transit District (SCRTD) in 1964. That same year, the Line #60 designation was given to freeway-express buses to Pomona; the local trips along Valley became Line #53, and those on Ramona were designated Line #53A. (Some Line #53 “Flyer” trips did use the freeway between Los Angeles and El Monte.)

In 1973 after the opening of the El Monte Busway (a high-occupancy vehicle lane built on former PE right of way in the middle of the San Bernardino Freeway), #53 and #53A were renumbered #401 and #402, respectively. Both #401 and #402 used the Busway between LA and El Monte. (Local service along Valley east of El Monte retained the Line #56 designation. It was renumbered #426 in 1976 and #76, its current number, in 1981.)

Restructuring and Renumbering

April 1976 marked a major restructuring in San Gabriel Valley bus service. SCRTD implemented many new lines, rerouted others, and renumbered just about every bus route. #401 (Valley) became #484, and #402 (Ramona) became #490.

SCRTD Line 484

But this was not just a renumbering. The new #484 received a reroute off Valley Blvd. to serve La Puente. #484 was also extended along Holt Avenue through Pomona, Montclair, and Ontario, terminating at the Ontario Airport. (Previously, service along Holt had been provided by Line #60. But the 1976 restructuring replaced #60 with new line #496, which mostly remained on the freeway in this area.) Service east of the county line (Mills Avenue) was operated under contract to Omnitrans, the transit provider in western San Bernardino County, and required an additional payment of Omnitrans’ base fare.

#490 was also extensively modified. The route segment between Covina and Pomona was eliminated, with no direct replacement (A new line #443 ran along the old #402 route as far as San Dimas, then looped back as #441 through Glendora. In 1983 these lines were renumbered #274 and 276, and were transferred to Foothill Transit in 1989). But #490 also gained coverage to new areas. First, in late 1977, #490 was extended south to Diamond Bar, terminating at Pacific State Hospital (Lanterman Hospital) by absorbing part of Line #449.

SCRTD Line 490

In 1980 it extended farther south through Diamond Bar, then onto the Orange Freeway (SR-57) to cross the Orange County line and terminate at Brea Mall, via Diamond Bar Blvd and the Orange Freeway (SR-57). (Transit service had not been provided in this corridor since the 1930s!) #490 added service to Cal State Fullerton in September 1981. The Brea-Fullerton portion was operated under a contract with the Orange County Transit District (OCTD), and an additional Orange County base fare was charged for rides to/from CSUF.

Foothillization

Arguably, SCRTD’s 1976 improvements initially over-served parts of the San Gabriel Valley. Buses ran every 20 minutes all day and into the late evening on streets where there was still very little development. This level of service was unsustainable, and SCRTD reduced services dramatically within a year or so. But as the area developed in the 1980s, the former service levels were never resumed. This angered local officials, prompting them to investigate an alternative to the SCRTD.

The Los Angeles County Transit Commission (LACTC), formed in 1976 to oversee all transportation development in the county, had a process of creating “transit zones”—alternative bus companies that could replace SCRTD in selected geographical areas. The cities of the eastern San Gabriel Valley applied to form a transit zone, to be known as “Foothill Transit,” then asked that the local SCRTD lines be transferred to the new agency. Foothill would save money by contracting with private bus companies; their buses cost less to operate because they paid drivers lower wages (about 2/3 what SCRTD paid).

The Foothill proposal was met with dismay by both SCRTD and the United Transportation Union, the bus drivers’ union. SCRTD officials, who had battled with the LACTC on various other issues, did not appreciate being told to relinquish any of its bus routes. And union officials were particularly incensed that its members would be replaced by lower-paid, presumably non-union drivers. (San Gabriel Valley bus routes were particularly popular with high-seniority drivers, since traffic was generally less heavy, and “issues” with passengers less common, than on the busier routes serving Central Los Angeles and other parts of the county. While no SCRTD driver would be laid off, they would be forced to drive less desirable routes.)

Over the protests of both SCRTD and its unions, most of the San Gabriel Valley bus lines were transferred to Foothill Transit between 1987 and 1992. However, four routes remained with SCRTD: #484, #490, #496, and #497. (What probably saved these lines for SCRTD was they all provided service outside of Los Angeles County; the new transit zone probably did not wish to negotiate new contracts with OCTD or Omnitrans.) #496 became primarily the responsibility of Omnitrans and the Riverside Transit Agency in 1990, and #497 became Foothill #699 in 2001, leaving #484 and #490 as the last remaining SCRTD routes in the otherwise all-Foothill world of the San Gabriel Valley.

SCRTD and LACTC merged in April 1993 to form the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (LACMTA, or, more commonly “Metro”). The merger had little, if any, effect on the two routes…for a while.

Omnitrans Takes Over Holt; Foothill Serves Brea

As mentioned earlier, #484 was the only bus line along Holt in Ontario—until Omnitrans expanded its Line #61 to run between the county line and the airport in 1995. Metro cut back the #484 accordingly. But Omnitrans, wanting a direct connection to the Downtown Pomona Metrolink station, extended #61 across the county line in 2000.

In June 2004 both #484 and #490 were cut back to Cal Poly Pomona. The portion of #484 between Cal Poly and Pomona, was merged with the section of #490 between Cal Poly and Brea. This new service, which was designated Line #684, lasted until June 2007, when it was transferred to Foothill Transit. Foothill rerouted the line along Mission Bl. and operated it as its Route #286.

The Silver Line and New Route Numbers (Dec 2009)

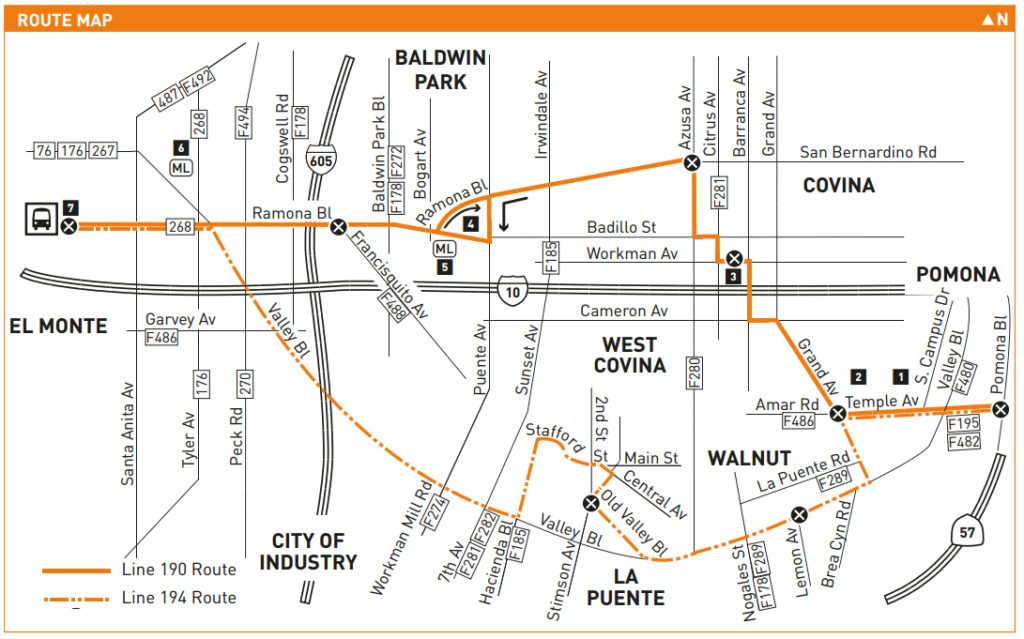

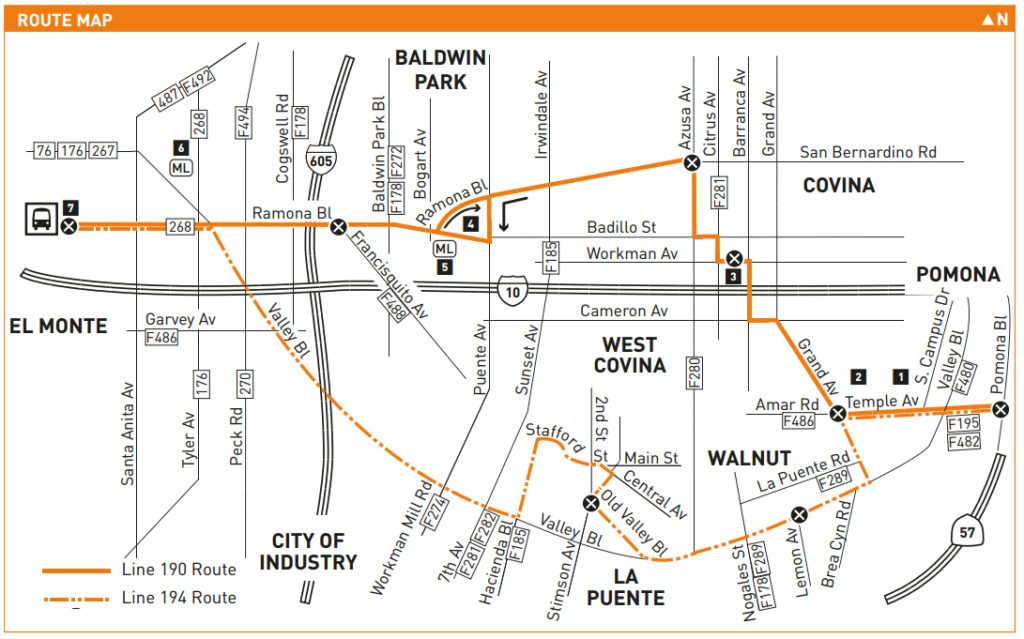

Map of Metro lines 190-194

San Gabriel Valley-bound express buses used the El Monte Busway’s lanes from Los Angeles to El Monte, then “fanned out” to serve different parts of the San Gabriel Valley. South Bay bus service using the Harbor Transitway, a similar facility on the Harbor Freeway, operated the same way. The Transitway’s version of El Monte Station was the Artesia Transit Center, near the Artesia Freeway (SR-91).

Since 1993, Metro had considered linking the express buses on the El Monte Busway to those on Harbor Freeway Transitway. Most buses serving either the San Gabriel Valley or the South Bay would no longer operate directly to downtown LA. Instead, passengers would transfer at either El Monte Station or Artesia Transit Center to the new “dual-hub” bus service. In December 2009, the new “Silver Line” began operation, ferrying passengers from El Monte, through Downtown Los Angeles, then south to the Artesia Transit Center.

#484 and #490 no longer served Downtown, only the segments between El Monte and Pomona. They were renumbered #194 and #190, respectively, in accordance with the numbering system for local, as opposed to express, bus routes.

Foothilization, Part Deux

Foothill Transit had been interested in acquiring the lines since 1995. Although its Comprehensive Operations Analysis from that year recommended Foothill take over #484 and #490, Metro was uninterested in relinquishing the two routes at that time.

But the Metro of the 2010s was not the all-bus SCRTD of the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. Metro now operated six rail lines (Red, Purple, Blue, Green, Gold, and Expo)—and planning and construction of new rail lines was underway. Metro would need resources—both drivers and funds—to operate the expanding rail system.

Over the past decade, Metro had been cancelling certain lower-performing bus routes, and allowing other operators (such as Foothill, Montebello, Santa Monica, Gardena, etc.) to acquire them. This was a cost-saving strategy allowing Metro to redirect resources to the heavily-used inner-city bus routes, and to the rail system.

During 2014-2015, Metro reviewed the ridership of each of its routes. It discovered that #190 and #194, combined, had a ridership of about 7,600 daily boardings on weekdays. (Weekend boardings were about half that.) To Metro, this figure was low compared with the average systemwide ridership. The agency recommended the two routes be discontinued, if another agency were willing to operate them.

“Another agency….hmm.” Guess which one was waiting in the wings?

On February 5, 2016, Metro held a public hearing regarding #190 and #194. Most of the people in attendance worried the lines would be cancelled with no replacement service; Metro officials reassured them that would not be the case. In fact, the transfer would be a win for most bus riders. Foothill offered lower fares ($1.25 vs. Metro’s $1.75), and riders needing to transfer between #190 or #194 and other buses would enjoy a free transfer, rather than the 50-cent interagency transfer between Foothill and Metro. Foothill also agreed to allow current Metro pass holders to ride free on #190 and #194 for a year after the transfer, and to preserve the current schedules.

The bus drivers’ union wasn’t happy about the proposed transfer at all. Already stung by the original Foothill takeover in the ‘80s and ‘90s, they vowed to fight to keep #190 and #194 with Metro.

After several weeks of negotiations, Metro and the union agreed to allow Foothill to take the two routes. In return, Metro would provide monetary bonuses for the affected union bus drivers, and would agree not to turn over any more bus routes to other agencies, or to any private contractors, for five years.

Foothill Transit bus on Line 194. C. P. Hobbs photo

Life under FTZ

As of this writing, I have heard very little in the press about Foothill’s operation of the #190 and #194. Has service become better or worse, or stayed about the same? Send me your comments…

References:

Bail, Eli, From Railway to Freeway: Pacific Electric and the Motor Coach.

Hobbs, Charles P. “From Los Angeles to the Inland Empire: A History of RTD Line #496”

Jones, Lionel. Los Angeles Bus Line History Book (updated route histories as of 2004)

Southern California Association of Governments. Transit Development Program.

(contains histories of bus routes up to 1971)

Scauzillo, Steve. “Foothill Transit wants to take over 2 Metro bus lines leaving from El Monte station.” San Gabriel Valley Tribune, December 12, 2014

Scauzillo, Steve. “Why Metro wants to discontinue 3 San Gabriel Valley bus routes.” San Gabriel Valley Tribune, January 1, 2016

Scauzillo, Steve. “Foothill Transit completes takeover of some discontinued San Gabriel Valley bus lines.” San Gabriel Valley Tribune, June 27, 2016

SMART (Bus drivers’ union) “GENERAL CHAIRMAN NEGOTIATES MAJOR DEAL OVER LINES 190 & 194”

Bus schedules, maps, agency agendas, etc. as appropriate

Changing of the guard: Foothill installs its own bus stop signs along the new routes.

Recent Comments