By Charles P. Hobbs

(Note: This article also appeared in the Transit Advocate, v. 28, no. 2)

In December 2019, reports came out about a mysterious viral disease in Wuhan, China. By mid-March 2020, this disease, now known as COVID-19 (COronaVIrus Disease 2019), had spread around the world. A global pandemic was declared. Workplaces and schools were shuttered, and people were asked to stay home in an effort to control the spread of the virus.

The shutdown caused an immediate effect on public transit systems throughout the United States. Ridership, already trending downward due to several factors, fell by about 80 percent as former riders complied with the shutdown orders given by local and state governments.

Transit agencies implemented various procedures to keep riders and drivers safe. To minimize contact with the driver, passengers (except disabled people) were asked to board and leave buses from the rear door. The area near the driver was blocked off, as were several seats in order to allow for social distancing. Fare collection was temporarily suspended. Later, a few transit systems placed transparent barriers near the driver’s area, allowing front-door boarding and fare collection to resume.

COVID-19 put the transit agencies in the odd position of actively discouraging ridership, in order to allow those traveling for essential functions–shopping for groceries, accessing medical services, or working at certain businesses deemed “essential”– to ride without fear of overcrowding. Some agencies limited the number of passengers allowed on a bus, again, to allow for social distancing between passengers. And, in compliance with statewide orders, riders and drivers were required to wear face masks.

What might transit look like, post-COVID?

Transit agencies generally provide two types of service:

Local buses on major arterial streets are most frequent (every 10 minutes or so) near downtown, or in inner city areas where residents historically lacked transportation. Buses tend to be less frequent (every 30 minutes, every hour, or even less frequent) in suburbs where there is a longer walk to the bus stops, and most residents have cars. Local buses also make frequent stops, perhaps every other block, slowing service for those passengers traveling longer distances.

Commuter express-type buses make a few stops in the suburbs, perhaps at a Park-and-Ride lot, then take freeways to their destination (usually downtown). This type of service, while attractive to suburbanites who would otherwise drive, is far more expensive for a transit agency to provide. Unlike a local bus, these buses pick up no fares along their express-running segments, and their routes may be too long to make multiple trips during the rush hour possible. Commuter express buses, with a few exceptions, run to downtown in the morning and back to the suburbs in the afternoon, making them useless for an inner-city resident needing to commute to a suburban job. Commuter express ridership is typically more affluent, and less ethnically diverse, than local bus ridership; this has brought up questions of equity.

Transit ridership had been dropping even before the COVID-19 emergency, due to so-called “transit-dependent” riders now having increased access to cars. As interest rates have dropped, financing an automobile has become easier for low-income individuals. Undocumented aliens can now get drivers’ licenses in California, and “rideshare” services, such as Uber and Lyft have gained in popularity. Slow local buses now have serious competition.

During the emergency, transit ridership is noticeably less “peaked.” Pre-COVID, transit usage was concentrated in the morning and afternoon, as most riders were commuting to and from traditional 8-5 jobs. Now, the demand curve is flatter, with those commuters mostly working from home. The journeys of current riders take place throughout the day: jobs with odd shifts, such as retail and warehouse jobs, essential shopping, and medical trips.

To adapt to this “new normal,” transit agencies are contemplating the following service modifications:

Enhancing the service provided in the central city, and nearby inner-city neighborhoods. Buses can be made to operate faster by removing stops, implementing signal preemption (automatically turning traffic lights green when a bus approaches), providing bus-only lanes, and allowing passengers to board at any bus door. To further speed service, buses would no longer have fareboxes; instead, fares would either be purchased from ticket machines located at stops (similar to those at Metro stations) or at retail stores. There is even the possibility of fareless transit–passengers board for free. Passenger comfort and security would be improved by providing additional bus shelters and digital schedule displays.

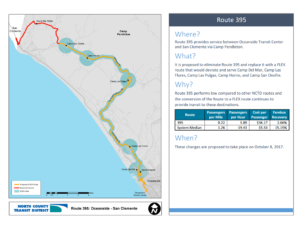

Commuter express services will undergo changes. Since many more people will be working from home, there will be less need for large fleets of buses to run into the central city in the morning, and back out in the afternoon. Instead, a network of express bus routes will run during the day, in all directions. Other destinations besides the central city will be offered, providing faster service for people working multiple jobs.

In less dense suburban areas, infrequent bus service may be replaced by “microtransit”–small vans that pick up passengers on request (via smartphone app, similar to Uber or Lyft). Pilot microtransit programs have already been implemented in parts of Los Angeles and Orange Counties.

On November 11, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use. While the COVID-19 pandemic will end, the disease has made an indelible mark on public transit, as well as on society in general.

Recent Comments